Although in the past I confessed to and made amends with mice research in obesity, I still have harbored skepticism. Mice are the gold standard! They reproduce quickly, live just long enough for experiments, and are all around a model organism.

But… they are not humans. Genetically similar, but still a rodent. Right? No no, now I am sounding scientifically illiterate. You’re right, they’re good. Are they? Yes. Yes?

Well finally it comes to the day where my misgivings may be vindicated. I feel a little relieved honestly. I hate being at conflict inside but I think it may be common among anyone with critical thinking capacity.

(I normally do not link to summary articles but this one by Science Daily covers 4 different research papers which I can leave to the discerning reader with journal article access to go through.)

The researchers did a genetic comparison between humans and mice.

In many cases, the investigators found that some DNA sequence differences linked to diseases in humans appeared to have counterparts in the mouse genome. They also showed that certain genes and elements are similar in both species, providing a basis to use the mouse to study relevant human disease. However, they also uncovered many DNA variations and gene expression patterns that are not shared, potentially limiting the mouse’s use as a disease model. Mice and humans share approximately 70 percent of the same protein-coding gene sequences, which is just 1.5 percent of these genomes.

For example, investigators found that for the mouse immune system, metabolic processes and stress response, the activity of some genes varied between mice and humans, which echoes earlier research. The researchers subsequently identified genes and other elements potentially involved in regulating these mouse genes, some of which lacked counterparts in humans. “We look at the mouse genome as a book with certain sections added and certain sections taken out by evolution. That may be a result of mouse and human adaptation to their respective environments,” said Dr. Ren, who is also a member of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, San Diego.

So now to the hot topic! The one that everyone especially in low carb, paleo, and vegetarian circles have been all atwitter about since it came out:

Red Meat Triggers Immune Reaction Which Causes Cancer

*horror music plays*

As I have just discussed: mice are questionable model organisms for immunity.

Secondly, 2/3 cases of cancer are caused by bad luck random DNA mutations which have no preventable cause. I’m frankly a little tired of how everyone freaks out over cancer prevention when it boils down to just luck sometimes. We all want to prevent cancer but for 66.7% of people who get it could not have prevented it. So there’s the 33.3% left here we’re talking about. However! This does not quell our fears of meat- 80% of colorectal cancers are attributable to environment. So let’s move on to talk about it.

There is also a bit of conflicting evidence here as well. This study points to rectal cancer (no association with colon) being associated with nitrosamine intake- including salted fish and Oriental pickled vegetables for a particular genetic variant. This study replaced carbohydrates with lean red meat and found no increase in inflammation in humans. This hugely detailed analysis has some pretty interesting things to say (CRC meaning colorectal cancer):

The COMA report (Department of Health, UK 1998) concluded that ‘there is moderately consistent evidence from cohort studies of a positive association between the consumption of red or processed meat and risk of colorectal cancer’. This report recommended that the current, average level of red and processed meat intake in the UK should not increase. Those with high levels of intake (>140 g per day) were recommended to reduce their consumption.

In the UK, the incidence of CRC has increased substantially over the past 35 years, yet red meat intake has declined by around 25% over the same period. A similar pattern has been seen in other European countries, such as Norway, where the risk of CRC has increased by 50% over the same period (Hill 2002).

And:

Hill (2002) suggests the following explanation for these apparently contradictory findings. In the large prospective study carried out by Hirayama (1990), dietary data were collected at recruitment and regular follow-up stages, and therefore a large amount of dietary information was gathered. The data were stratified into four intake groups for meat (daily, often, sometimes and never consumed) and similarly analysed for vegetable intake. Daily meat consumers were found to have a much higher incidence of CRC than those who never consumed meat, with the other two groups intermediate. But simply looking at meat hides more complex relationships. For those individuals who never ate vegetables, meat intake was positively associated with CRC, however, for those who consumed green-yellow vegetables daily, there was an inverse association between meat intake and CRC risk. This suggests that meat intake may only be a risk factor in those who do not eat sufficient amounts of foods that are considered to be protective (Hill 2002).

Further support for this hypothesis comes from a prospective study carried out in America with a cohort of the Adventist Health Study (Singh & Fraser 1998). Singh and colleagues found that individuals with a high meat intake, a low intake of legumes (pulses) and a high body mass showed a three-fold increase in risk of colon cancer, relative to other patterns of these variables.

This may also help explain why many Mediterranean countries, which have a higher meat intake than the UK (see Table 8), have lower rates of CRC mortality, since vegetable and fibre intake tends to be much higher in Mediterranean countries than in northern European countries. Moreover, this could also help explain why meat intake only appears to be a risk factor in the highest intake groups (i.e. more than 140 g per day) as this level of intake could override the effect of protective factors provided by plant foods in the diet (Hill 2002).

Finally:

The recent EPIC paper also looked at whether the increased risk of CRC with high intakes of red and processed meat could be partially explained by low fibre intakes. Those participants with a high intake of red and processed meat who also had a high (>26 g per day in women and >28 g per day in men) intake of fibre were shown to have a lower risk of CRC (HR = 1.09, 95% CI: 0.83–1.42) than those with a high intake of red and processed meat and a medium or low (<17 g per day) intake of fibre (HR = 1.5, 95% CI: 1.15–1.97). In fact, the risk reduction associated with a high fibre intake was shown to be similar for all levels of red and processed meat intake (Norat et al. 2005). These results suggest that the increased risk which appears to be associated with high intakes of red and processed meat is attenuated in individuals who include plenty of dietary fibre from fruit, vegetables and wholegrain cereals in their diet.

So nothing new, nothing revolutionary- get your fiber.

Cancer is not ‘up to luck’. This would imply a shift in luck between pre-agricultural & agricultural societies.

My daughters were watching a youtube video in which a mathematician was explaining that the sum of all integers going to infinity was 1/12. The man was obviously well educated and made a logical proof of his assertion. However, I only need to go out into my hayfield and begin to pick up rocks 1+2+3+4 etc to know that I can never carry enough to get to 1/12.

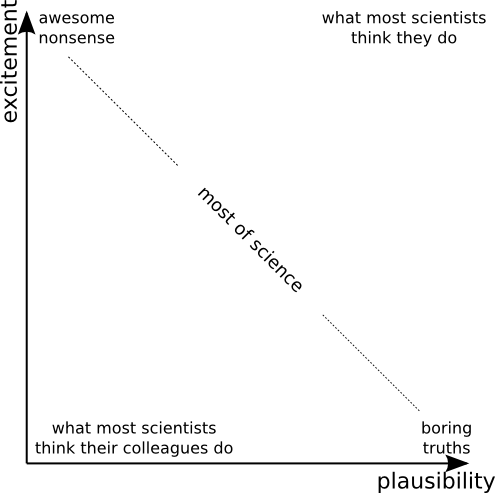

Research results and clinical results frequently do not align. I shudder as medicine moves toward “evidence based” standards.

I wonder if a daily dose of Metamucil or other fiber supplement would impart the same benefits. Thoughts?

Personally I think some fiber is better than no fiber but this article appears to say that where the fiber comes from matters.

I’m no scientist but nitosamine is probably spelled nitrosamine.

Thanks Hazel! My spell checker *cough* Michael *cough* missed it. 🙂

When I first saw this big whoop in the news, my first reaction was to consider that in general mice mostly seed, grain, greens/fruits. If they are primarily herbivorous it would make sense that they would have some reactions to meat that human omnivores do not.